Entrepreneurship in Education

More than one billion people today are between 15 and 25 years of age and nearly 40 per cent of the world’s population is below the age of 20 (ILO, 2007). Eighty-five per cent of these young people live in developing countries where many are especially vulnerable to extreme poverty (ILO, 2007). The International Labor Office estimates that around 88.2 million young women and men are unemployed throughout the world, accounting for 47 per cent of all the 185.9 million unemployed persons globally, and many more young people are working long hours for low pay, struggling to eke out a living in the informal economy.

The challenge facing the world today is to make education meaningful and more inclusive to this set of young people around the globe (UNICEF 2000, UNESCO 1996, 2000, 2004 and 2005) Education is widely recognized as one of the most critical means of defeating the challenges of development, poverty, and inequality. However, the current quality of education in developing economies (especially in South Asia) leaves much to be desired.

The definition of entrepreneurship involves creation of value through fusion of capital, risk taking, technology and human talent. It is a multidimensional concept. The distinctive features of entrepreneurship over the years are:

– Innovation, – A Function of high achievement,

– Organization building, – Group level activities,

– Managerial skills and leadership, – Gap filling activity

– Entrepreneurship – An emerging clas

For Scientist, ‘theory’ refers to the relationships between facts. In another words, theory is some ordering principles. There are various theories of entrepreneurship which may be explained from the viewpoints of economists, sociologists and psychologists. These theories have been supported by various thinkers over two and half centuries.

۱٫ The idea of infusing entrepreneurship into education has spurred much enthusiasm in the last few decades. A myriad of effects has been stated to result from this, such as economic growth, job creation and increased societal resilience, but also individual growth, increased school engagement and improved equality. Putting this idea into practice has however posed significant challenges alongside the stated positive effects. Lack of time and resources, teachers’ fear of commercialism, impeding educational structures, assessment difficulties and lack of definitional clarity are some of the challenges practitioners have encountered when trying to infuse entrepreneurship into education.

۲٫ This report aims to clarify some basic tenets of entrepreneurship in education, focusing on what it is, why it is relevant to society, when it is applied or not and how to do it in practice. The intended audience of this report is practitioners in educational institutions, and the basis of this clarification attempt consists primarily of existing research in the domains of entrepreneurship, education, psychology and philosophy. Where research is scarce the author of this report will attempt to give some guidance based on own conducted research.

۳٫ What we mean when we discuss entrepreneurship in education differs significantly. Some mean that students should be encouraged to start up their own company. This leans on a rather narrow definition of entrepreneurship viewed as starting a business. Others mean that it is not at all about starting new organizations, but that it instead is about making students more creative, opportunity oriented, proactive and innovative, adhering to a wide definition of entrepreneurship relevant to all walks in life. This report takes the stance that a common denominator between these differing approaches is that all students can and should train their ability and willingness to create value for other people. This is at the core of entrepreneurship and is also a competence that all citizens increasingly need to have in today’s society, regardless of career choice. Creating new organizations is then viewed as one of many different means for creating value.

۴٫ Why entrepreneurship is relevant to education has so far primarily been viewed from economic points of view. This has worked fairly well for elective courses on higher education level, but is more problematic when infusing entrepreneurship into primary and secondary levels of education for all students. Here, a much less discussed but highly interesting impact that entrepreneurship can have on education is the high levels of student motivation and engagement it can trigger, and also the resulting deep learning. This report will argue that in line with a progression model of when to infuse entrepreneurship into education, the question of what effects to focus on should also be progressively changing over time in the educational system. Students can become highly motivated and engaged by creating value to other people based on the knowledge they acquire, and this can fuel deep learning and illustrate the practical relevancy of the knowledge in question. Those students that pick up strong interest and aptitude for value creation can then continue with elective courses and programs focusing on how to organize value creation processes by building new organizations. Such an approach has far-reaching implications on how to plan, execute and assess entrepreneurship in education, and they will be discussed in this report.

۵٫ When we should infuse entrepreneurship into education is increasingly clear in theory, but in practice much remains to be done. In theory we should start at an early age with a wide definition of entrepreneurship embedded across the curriculum and relevant to all students, preferably in preschool and primary school. Later in the educational system we should complement with a parallel voluntary and more business-focused approach, applying a more narrow definition of entrepreneurship. In practice however, explicit entrepreneurial activities on primary education levels are rare. And on secondary and tertiary levels most initiatives are business start-up focused, lacking embeddedness into other teaching subjects. In vocational education and training, entrepreneurial activities are frequent in terms of value creation for other people, but they are seldom connected to the entrepreneurship domain and its tools, methods and processes for creating value.

۶٫ How to make students more entrepreneurial is probably the most difficult and important question in this domain. Many researchers claim that the only way to make people more entrepreneurial is by applying a learning-by-doing approach. But then the question of learning-bydoing-what needs to be properly answered. There is increasing consensus among researchers that letting students work in interdisciplinary teams and interact with people outside school / university is a particularly powerful way to develop entrepreneurial competencies among students. However, if this kind of experiential learning based activity is to be classified as entrepreneurial, some kind of value needs to be created for the people outside school or university in the process. It is not sufficient to just interact with outside stakeholders without a clear end result. For this to work in practice, teachers can draw on the entrepreneurship domain which contains many useful value creation tools, methods and processes. This report will outline some of them.

۷٫ Future challenges and opportunities abound in entrepreneurial education. This report will try to outline some of them through a final section in each of the following chapters.

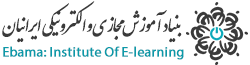

Although the current popularity of entrepreneurial exploits would tend to make you think that it is a twentieth or twenty first century phenomenon, but it’s not like this. Early in the eighteenth century, the French term entrepreneur was first used to describe a “go-between” or a “between-taker.” Richard Cantillon, a noted economist and reknowned author in the 1700s, is regarded by many as the originator of the term entrepreneur. Cantillon used the term to refer to a person who took an active risk-bearing role in pursuing opportunities. Late in the eighteenth century, the concept of entrepreneurship was expanded to include not only the bearing of risks but also the planning, supervising, organizing, and even owning the factors of production. The nineteenth century was a fertile time for entrepreneurial activity because technological advances during the industrial revolution provided the impetus for continued inventions and innovations.

Then, toward the end of the nineteen century, the concept of entrepreneurship changed slightly again to distinguish between those who supplied funds and earned interest and those who profited from entrepreneurial abilities. During the early part of the twentieth century, entrepreneurship was still believed to be distinct and different from the management of organizations. However, in the mid-1930s the concept of entrepreneurship expanded. That’s when economist Joseph Schumpeter proposed that entrepreneurship involved innovations and untried technologies or what he called creative destruction, which is defined as the process whereby existing products, processes, ideas, and businesses are replaced with better ones. Schumpeter believed that through the process of creative destruction, old and outdated approaches and products were replaced with better ones.

Through the destruction of the old came the creation of the new. He also believed that entrepreneurs were the driving forces behind this process of creative destruction. They were the ones who took the breakthrough ideas and innovations into the marketplace. Schumpeter’s description of the process of creative destruction served to highlight further the important role that innovation plays in entrepreneurship. As our earlier definition of entrepreneurship showed, the concepts of innovation and uniqueness are (and always have been) integral parts of entrepreneurial activity.

The final development from the twentieth century we’ll look at is Peter Drucker’s contention that entrepreneurship involves maximizing opportunities. Drucker is a well known and prolific writer on a wide variety of management issues. What his perspective added to the concept of entrepreneurship is that entrepreneurs recognize and act on opportunities. Drucker proposed that entrepreneurship doesn’t just happen out of the blue but arises in response to what the entrepreneur sees as untapped and undeveloped opportunities. Although .we’ve looked at only a small portion of entrepreneurship’s long and colourful past, keep in mind that the history of entrepreneurship continues to unfold. Its history is still being written today. In the early years of the twenty-first century, researchers continue to study entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship. Although no generally accepted theory of entrepreneurship has emerged from these studies.

جهت ثبت نام در دوره آموزشی مدیریت کارآفرینی بر روی تصویر فوق کلیک نمایید

دوره غیر حضوری است و محتوای الکترونیکی در قالب CD یا DVD به آدرستان ارسال می گردد

پس از پایان گواهی و مدرک معتبر دوره آموزشی مدیریت کارآفرینی با قابلیت ترجمه رسمی دریافت می نمایید

مشاوره رایگان: ۰۲۱۲۸۴۲۸۴ و ۰۹۱۳۰۰۰۱۶۸۸ و ۰۹۳۳۰۰۲۲۲۸۴ و ۰۹۳۳۰۰۳۳۲۸۴ و ۰۹۳۳۰۰۸۸۲۸۴ و ۰۹۳۳۰۰۹۹۲۸۴

A coordinated and comprehensive theory of entrepreneurship is yet to come. Mean while lets try to understand the following theories of entrepreneurship propounded by the different eminent social thinkers:

۱٫ Innovation Theory of Schumpeter

۲٫ Need for Achievement Theory of McClelland

۳٫ Leibenstein’s X-efficiency Theory

۴٫ Risk Bearing Theory of knight.

۵٫ Max Weber’s Theory of Entrepreneurial Growth

۶٫ Hagen’s Theory of Entrepreneurship

۷٫ Thomas Cochran’s Theory of Cultural Values

۸٫ Theory of Change in Group Level Pattern

۹٫ Economic Theory of Entrepreneurship

۱۰٫ Exposure Theory of Entrepreneurship.

۱۱٫ Political System Theory for Entrepreneurial Growth.

The two most frequent terms used in the field of entrepreneurship in education are enterprise education and entrepreneurship education. The term enterprise education is primarily used in United Kingdom, and has been defined as focusing more broadly on personal development, mindset, skills and abilities, whereas the term entrepreneurship education has been defined to focus more on the specific context of setting up a venture and becoming self-employed (QAA, 2012, Mahieu, 2006). In United States, the only term used is entrepreneurship education (Erkkilä, ۲۰۰۰).

Some researchers use the longer term enterprise and entrepreneurship education (See for example Hannon, 2005), which is more clear but perhaps a bit unpractical. Sometimes enterprise and entrepreneurship education is discussed by using the term entrepreneurship education only, which however opens up for misunderstanding. Erkkilä (۲۰۰۰) has proposed the unifying term entrepreneurial education as encompassing both enterprise and entrepreneurship education.

The most common reason that researchers and experts promote entrepreneurial education is that entrepreneurship is seen as a major engine for economic growth and job creation (Wong et al., 2005). Entrepreneurial education is also frequently seen as a response to the increasingly globalized, uncertain and complex world we live in, requiring all people and organizations in society to be increasingly equipped with entrepreneurial competencies (Gibb, 2002). Besides the common economic development and job creation related reasons to promote entrepreneurial education, there is also a less common but increasing emphasis on the effects entrepreneurial activities can have on students’ as well as employees’ perceived relevancy, engagement and motivation in both education (Surlemont, 2007) and in work life (Amabile and Kramer, 2011). Finally, the role entrepreneurship can play in taking on important societal challenges (Rae, 2010) has positioned entrepreneurial education as a means to empowering people and organizations to create social value for the public good (Volkmann et al., 2009, Austin et al., 2006).

The strong emphasis on economic success and job creation has indeed propelled entrepreneurial education to a prominent position on higher education level, but not as an integrated pedagogical approach for all students on all levels. So far primary focus has been on elective courses and programs for a few secondary education and university students already possessing some degree of entrepreneurial passion and thus self-selecting into entrepreneurial education (Mwasalwiba, 2010). The emphasis on economic effects has so far hampered a widespread adoption of entrepreneurial education in the remaining parts of the educational system. Instead it is often viewed as a “dark threat” by teachers, stating that the “ugly face of capitalism” is now entering educational institutions (Johannisson, 2010, p.92). The stated necessity of all people to become more entrepreneurial due to globalization and increasing uncertainty on the market has spurred significant activity on policy level, but has not yet transferred into wide adoption among teachers on all levels of education.